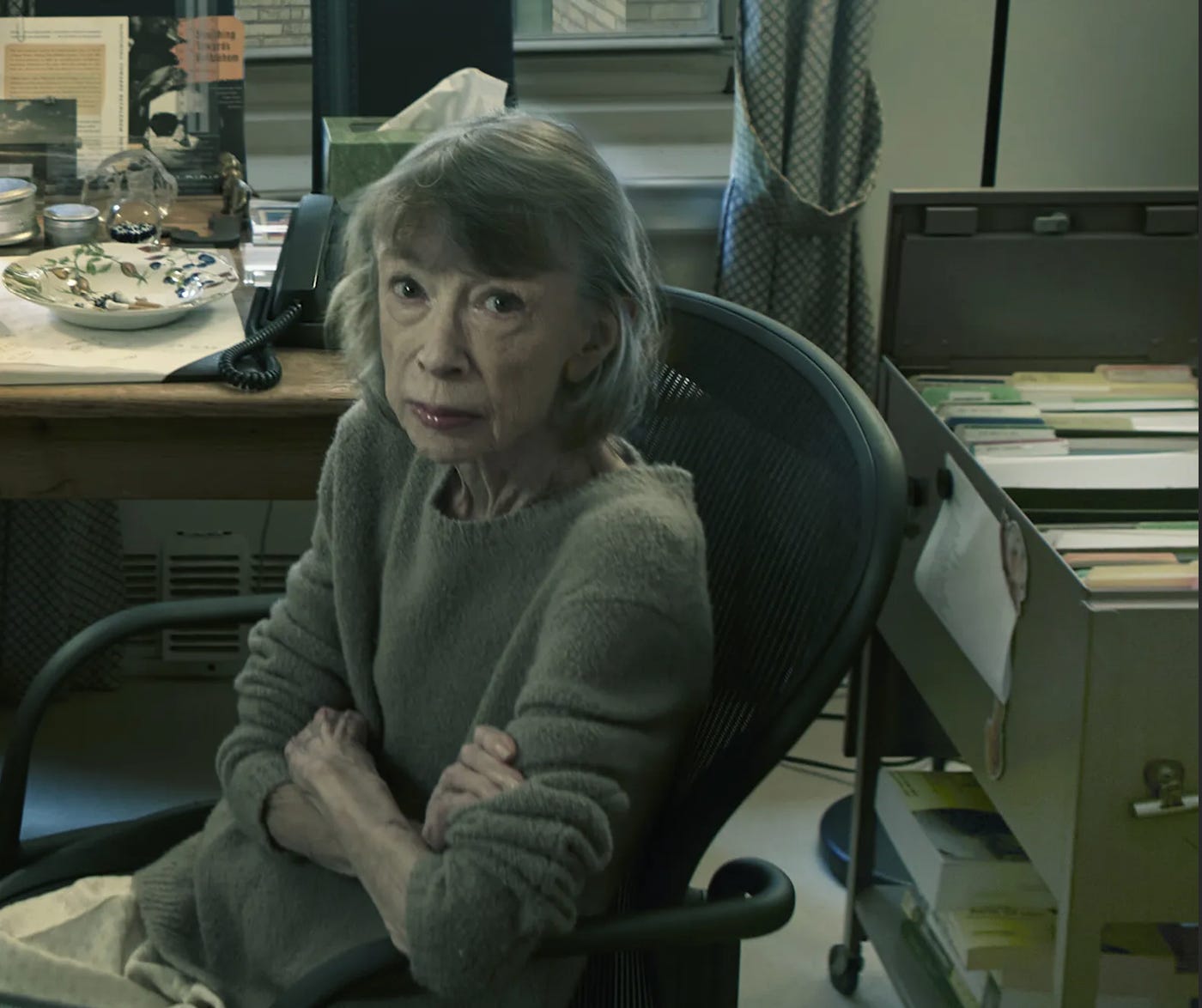

Joan Didion is looking at you, my brain hisses. She’s peering out from the cover of Notes to John, arms crossed—in discomfort? in annoyance?—shoulders slightly hunched. It’s like she knows I’m avoiding her. It’s not that I’m not reading. I read a silly 15,000 page vampire trilogy in a single week to put space between myself and the task. After the first few pages, I stopped. I started. I stopped. I retreated to the vampires. Closing the book, it was impossible to ignore the full-body discomfort creeping through me.

Notes to John, published posthumously in May, signals what appears to be the last new Joan Didion book. The slim volume comprises Didion's typed notes from her therapy sessions meant to be shared with her husband John Gregory Dunne. That in itself might be a bit odd, but Didion entered therapy at the request of their daughter Quintana. Didion’s meticulous notes reveal Quintana’s struggles with alcoholism, her tendency to play victim, and her difficult relationship with her parents, as well as Didion’s anxious concern and careful attempts to improve elements of their relationship in the hope that might remove some of Quintana’s burdens.

I’ll freely admit that my affection for Joan Didion is tinged parasocial, but I do not feel that I am entitled to these notes, nor is anyone else. Let’s face it: there’s something incredibly off putting about reading someone’s therapy notes. Even if they’re Joan Didion’s. Even if she typed them up herself. Anyone familiar with Didion’s writing would be quick to identify that these are notes, not pieces; notes, not a book. Why have we published this? It feels invasive. It feels grasping. It feels like the subject of an ethics essay.

As a writer, Didion is characterized by control. She revels in it: carefully crafted sentences, rolling parallelism and rhythmic repetition to press a point, the calculated glimpses of Didion the author so pointed that the reader can’t escape its intentionality. Didion was choosing how much of her we were allowed to access. Following the abrupt death of her husband and daughter, Didion wrote two memoirs that spoke to her relationship with them and the events surrounding their passing. Blue Nights discussed Quintana’s illness and death, yet it felt purposefully obfuscated at times. Again: purposefully. With the publication of Notes to John, the veil is lifted and intensely personal, direct references to her daughter’s struggles with addiction are in print. Now, somehow, access has turned into freefall.

From an academic standpoint, this look into Didion’s inner life fills gaps in my interpretation of Blue Nights—confirming previous hypotheses about Quintana and their relationship, as well as the inspiration for characters like Marin in A Book of Common Prayer and Jessie in Democracy. There is value here—especially for scholars writing on Blue Nights, The Year of Magical Thinking, or those analyzing mother daughter relationships across Didion’s oeuvre. However, the contents of Notes to John makes me even more adamant that if Didion had wanted us to read these notes, know these private things, she would have included them in Blue Nights as she reflected on Quintana.

There are few footnotes in the book. The editorial team was inconsistent in providing context, leaving readers to fill in the gaps on their own, leading me to infer that this is not intended as a scholarly edition. These typed notes, found in a filing cabinet in Didion’s office, were donated along with her other papers to the NYPL with open access. Again, why this was published?

With distance, would reading these notes feel less invasive? Possibly. Imagining myself a scholar fifty years in the future, I can see the value. Yet as a reader? Nope. These are notes through and through. There is little literary value here outside of the biographical context they might provide. It’s easy to shrug off responsibility by saying Didion knew this would happen. After all, she was one of our most celebrated writers: surely she knew what would happen to her papers after her death. If she didn’t want the notes to be found, she should have destroyed them.

It’s an easy argument to make—one that relieves the living of any ethical culpability. It’s also fairly robotic. Can you imagine tossing your private papers into the fire (or more likely the shredder), actively engaging with your imminent death in this way? Let’s also consider John and Quintana’s deaths in 2003 and 2005. Would destroying these notes feel too painful? I’m no Joan Didion, but even if I were…I wouldn’t want my private thoughts published in this way; I would also feel incapable of removing even more of my beloved family from my world—even if they were only ciphers on the page.

The US publishing industry may be facing challenges, but does that mean we toss aside all scruples in favor of sales? Penguin Random House describes Notes to John as “an extraordinary work from the author of The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights,” but let’s call it what it is: a crass money grab.

Is froyo a recession indicator?

Apparently lawyers tend to love Jane Austen. Personally, I thought everyone did?