I tried to recreate the image I held in my head. A curved arch, the tessellating geometry of the tiles, hammered brass, and carved stone. Photograph to imagination to…whatever this was trying to be. Translating the door from my laptop’s glowing screen to my paper, I erased and redrafted until my lines were approaching straight. They weren’t perfectly perpendicular, mind. Each diamond tile was unique to its peers, but that didn’t bother me. This was an approximation I could live with. Satisfied, I flipped my drawing onto its back and scribbled hard until the rectangle glowed with a uniform charcoal sheen, transferring a ghostly impression onto the block. A translation of a translation.

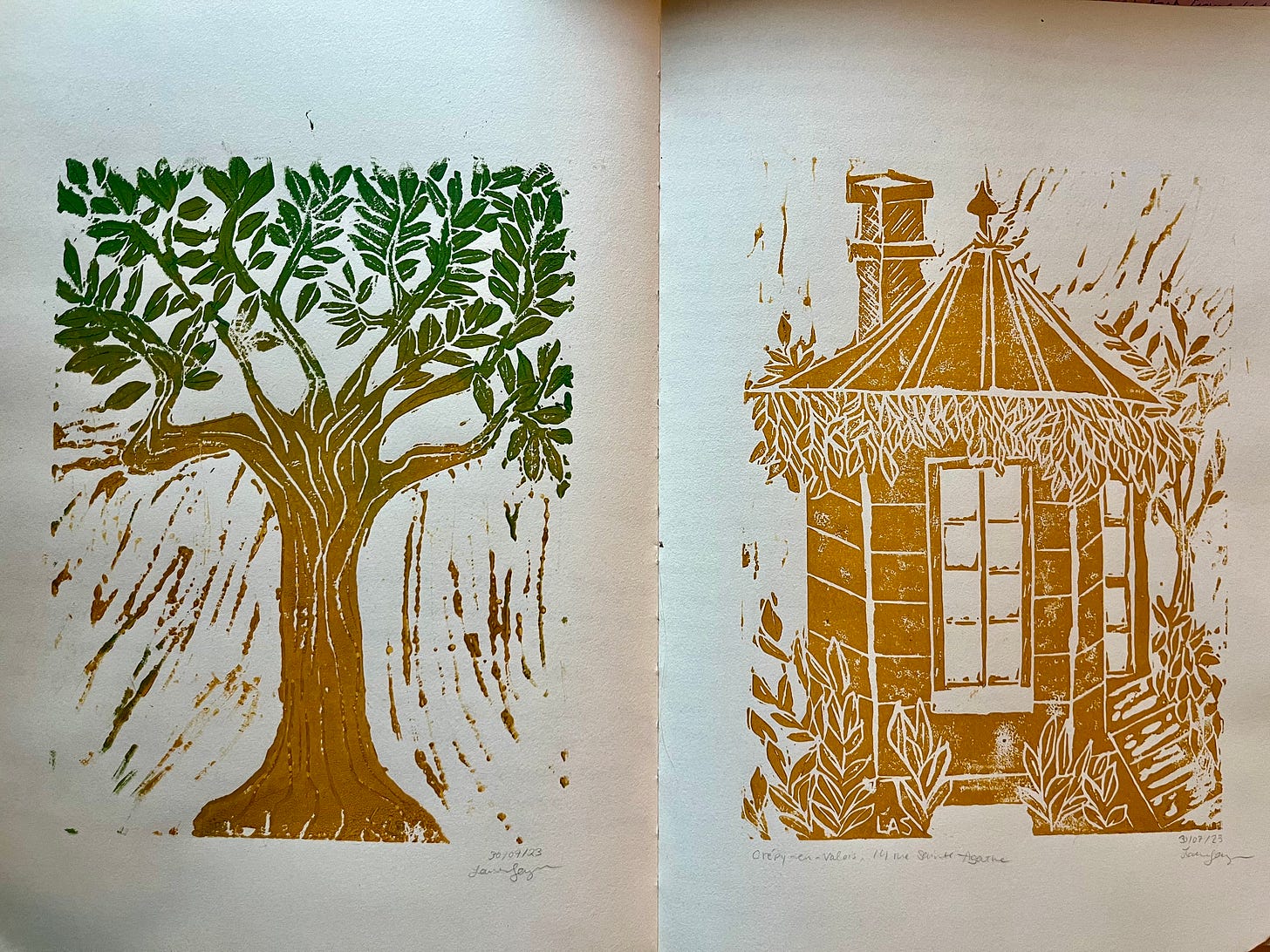

My mother is the artist in our family. Her college diary is filled with fragments of poetry and watercolors pasted into its pages for safekeeping. My favorite of her finished paintings hung in my room growing up: a tree silhouetted against a fiery sunset. As a teenager, the painting struck me as a kind of romantic ideal—the passion of the skies juxtaposed with the delicate fragility of the dark, empty branches and rolling fields. Her painting was a place I wanted to go; the person I would become under its branches was someone I couldn’t wait to meet—a canvas as unlimited potential. My mother encouraged my pursuits in visual mediums, but I was a woman of words. Curled up with a book, I felt more at home in the space between the story on the page and its images projected in the theater of my imagination. Still, I dabbled. I doodled. I painted. I drew. I wanted to be good, but it didn’t plague me when I wasn’t. I was having fun, and fun was its own reward. My mother was the artist; I was the writer.

Wandering through the Melrose Trading Post, I flicked through the racks of vintage dresses, tried on hats, and bought a charm featuring a roller skating bear melted down from reclaimed brass bullet casings. Turning the corner, I lingered in front of a stand selling 1930s woodcut prints. They were in monochrome red or black ink on cream paper, protected by plastic film. The dealer manning the booth described how the images were carved into wooden blocks, and the precision of the intricate lines of white space flared brighter in my mind. The light shining on a flapper’s finger wave now felt profound. They were too expensive for my allowance and their technique was beyond me, but their memory stayed, stark and stylized.

A decade later, a poet I met in Paris started posting her art. She documented her early prints—little more than white line drawings in a sea of black ink—but I was entranced, remembering Saturdays on Melrose. Linocut, she told me, when I asked. Her work grew from portraits and sketches to intricate illustrations of The Odyssey. A few years later, I met a beautiful artist on holiday in Tbilisi. She too made linocut prints. I knew it was my turn then—I can’t resist the rule of three.

Start with something easy, I said, start with something small. I did not. Sketching Joan Didion’s face onto the gummy beginner’s block, I tried to think about negative space. I tried and failed, starting again. Sitting cross legged on the floor, I squeezed ink into the trough. Dragging my roller through the ink, I slicked the block wet and pressed it against the pages of my journal. My prints were bad: too wet, too dry, streaked with oil from my fingerprints, then one that was just right. I loved it. Taking out a fresh block, I began again. I carved portraits of my cat, trees and flowers, a living room with a crooked checkerboard floor, a questionable Diana the Huntress, and a backyard folly.

Linocut felt different than writing. My creativity was free, limited by skill, but untethered to my ego. Carving out the negative space felt meditative. When I failed to follow the pencil outlines with precision, I kept going. So it would be a bit crooked. I was more interested in the wider picture, what it would look like inked, what new technique I could try. In linocut, I wasn’t trying to be anything or elicit emotional impact. It was pure play, an exercise in creativity and materiality that didn’t feel so do or die. If my first print didn’t turn out, I could ink five more. I usually did.

Writing, I agonize over the ideal word, the right amount of tension, the lines of dialogue that are still just okay. I’m caught in looping self-flagellation. If it’s not done right, is it worth doing at all? The staggering heft of living up to the idea in my head feels paralyzing. Can it be perfect the first time you type out a scene? No. Does that matter to my inner monologue? Also, no. Pushing past the first draft and cleaning up the glaring should-have-known-better mistakes of the second should be added to the Herculean Labors. Ideas are luminous, but immaterial. I know this. Still, I hold myself hostage over living up to the allure of potential.

As the hours passed, my Moroccan door began wavering into focus. Delicately digging the tool into the lino, I shifted the block to get a better angle. Fleetwood Mac’s twelfth album looped. I shook my cramping hand out of its claw. I rolled my shoulders back and then hunched over my work again. My door was cursed with faulty symmetry, but it was recognizable as the image I held in my head. More or less. That was enough.

It didn’t hurt — at first — when the blade slipped and jammed into my thumb. I felt the blunt resistance of bone, the numbness of slamming your elbow into a cabinet. I didn’t take it seriously until the slit in my skin began oozing blood and wouldn’t stop. The cut was deep, but I couldn’t stomach too close of a look. Holding my hand above my head, I flitted around my apartment to “Tusk,” hoping three minutes and thirty-seven seconds would be enough to make it stop. I had enough on my mind without impromptu bloodletting at midnight, but here we were.

In the morning, my thumb felt puffy and stiff. It resisted my commands to bend, but the bleeding had stopped. Vowing to be more careful, I reclaimed my seat at the table. Scrubbing at the block with my eraser, I lifted the pencil marks I’d missed. It was another thing entirely now, all evidence of my mistakes cleared. I tried to read the image, but I knew I needed ink for that. Turquoise, I decided, running the roller vertically and horizontally through the blue puddle and over my block until it was evenly coated. I placed it face down on a blank sheet of paper—the first kiss.

Without a press, I layered my fattest books: The Norton Shakespeare on top of The Journals of Sylvia Plath 1950–1962 on top of Ainsi de Suite on top of The Dolphin Letters. Standing on the pile, I stretched into an arabesque—my sentimental nod to Edie Sedgwick—and counted fifteen seconds. Removing the books, I gently peeled the paper away from the block. I’d missed a spot, the printed image faded and fuzzy in parts. I squeegeed the roller through the ink and began again. When I was done, I had ten doors drying on every flat surface a cat couldn’t reach.

I still have a mark on my left thumb, a small red dash in a jaunty angle over my knuckle. In its center, the thin white line of the scar is precise. Perfect, one could say.

Speaking of Tusk, sometimes I crave mess. Enter, Fleetwood Mac lore.

Tess Little revisits The Webster Apartments, one of New York’s all-female boarding houses, for The Paris Review.

“Heartbreak is one thing, my ego’s another/I beg you don’t embarrass me, motherfucker.” — From Taylor Swift to Sabrina Carpenter, the pop girlies are acknowledging the potential fallout tied to public association with their boyfriends. Carpenter’s new video does away with subtext entirely in casting Barry Keoghan.

The writers are rounding off the final days of Jami Attenberg’s #1000WordsOfSummer challenge. If you’re looking for a little encouragement, guest writers have offered their thoughts on approaching writing as a daily practice. 10/10 recommend.