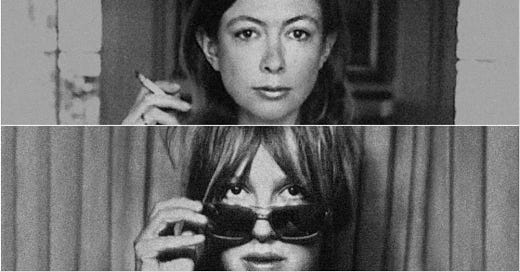

The most anticipated book of the season (in my circles anyway) is undoubtedly Lili Anolik’s Didion & Babitz. A compelling, compulsive read, Didion & Babitz explores the fraught connection between Joan Didion and Eve Babitz fully unearthed following Babitz’s death and the donation of her papers to the Huntington Library. While we know the women ran in similar circles, Didion & Babitz reveals the depth of their friendship: how Joan launched Eve’s career, how she edited Eve’s first book, how Eve resented her for both of these things, how their friendship shattered, and how Eve was unable to let it go.

Anolik is known for her fierce investigative reporting that leaves no stone unturned. She delivers the premium gossip—the good stuff. You want to know what went on at Bennington College or what Michelle Philips has to do with the pivotal scene in Play It As It Lays? Lili Anolik’s got you. She’s responsible for bringing Eve Babitz back into the cultural zeitgeist in 2015 with an impassioned Vanity Fair feature, after all. Without her, would Eve Babitz remain a footnote—known primarily as the “dowager groupie” of the 1960s and 70s? Anolik argues that Eve would have resurfaced eventually, but I still think it’s key to give Anolik her due. A finder’s fee, of sorts.

If you’re an avid reader of Didion and Babitz, some of the book will be a pleasant retread—though there is plenty of fresh material to pique your interest. Anolik’s tone and style will have you leaning in, hungry for more. Unfortunately, despite the jacket copy declaring “Joan Didion, revealed at last,” we learn very little about Joan. The vast majority of Anolik’s attention goes to Eve. This could be forgivable if Anolik wasn’t relentless in her pursuit of knocking Joan down a peg. Whenever an event could be analyzed from an uncharitable perspective, Didion’s motivations are picked apart.

However, Didion & Babitz does include some sparkling contributions to the conversation. The highlights? Eve’s unsent letters—namely two: one to Joan Didion and another to Joseph Heller. In them, Eve pulls off her carefree mask and we see just how urgent her feelings are—about her writing, her reputation, her uncertain future, and frustration with the way women writers were playing a rigged game. If you wanted a chance at success, you had to be strategic. You had to smuggle yourself into the ol’ boy’s club. Both Eve Babitz and Joan Didion did this in their own respective ways: Joan with her cool perception and almost masculine prose; Eve with her disarming, effervescent voice and carefree sexuality.

In her unsent letter, Eve takes Joan to task for her assumption of the masculine posture of what a good, lauded East Coast Elite should be. She’s not wrong. In her letter, the letter that inspired Anolik to write this book, Eve goes for the jugular. I’ll give you an excerpt here:

Just think, Joan, if you were five feet eleven and wrote like you do and stuff—people’d judge you differently and your work, they’d invent reasons…Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan? Would you be allowed to if you weren’t physically so unthreatening? Would the balance of power between you and John have collapsed long ago if it weren’t that he regards you a lot of the time as a child so it’s all right that you are famous. And you yourself keep making it more all right because you are always referring to your size. And so what you do, Joan, is live in the pioneer days, a brave survivor of the Donner Pass, putting up the preserves and down the women's movement and acting as though Art wasn’t in the house and wishing you could go write.

It embarasses me that you don’t read Virginia Woolf. I feel as though you think she’s a “Woman’s novelist” and that only foggy brains could like her and that you, sharp, accurate journalist, you would never join the ranks of people who sogged about in The Waves. You prefer to be with the boys snickering at the silly women and writing accurate prose about Maria who had everything but Art. Vulgar, ill bred, drooling, uninvited Art. It’s the only thing that’s real other than murder, I sometimes think—or death. Arts’ the fun part, at least for me. It’s the salvation.

After reading that, I’d write a book about them too—just not this one.

Anolik gets it wrong. Biased, she looks uncharitably towards Joan, tearing one woman down to lift up the other. Ultimately, the problem isn’t with Anolik’s bias towards Eve Babitz. She states it clearly, lovingly, and I understand it. I love Eve, too. I love Eve for her effortlessness on the page (an effortlessness that is anything but), her adoration of glamor, Hollywood mythology, and viewing life through the lens of cinema and fairy tales. But I also love Joan. Reading Joan, I feel extremely awake—my emotions and intellect equally engaged, I see the world in new ways through her eyes. I love both of these writers with a passion that drove me to make them the subject of my Master’s thesis. My argument? That there was no competition; Joan Didion and Eve Babitz are two sides of the same coin—two privileged white women chronicling the zeitgeist through contrasting voices and themes that captured the pivotal ways in which American culture was shifting. There is no winner, other than their readers.

Anolik argues that her motivation is adoration that borders on obsession—sometimes leading to destructive revelations. But if Anolik is a “Literary Assassin,” then how can she have such beef with Joan Didion for that same passion for her craft? Anolik is biting when it comes to Joan. Recounting a letter from a source saying that Joan was desperate to know her editor’s opinion as to whether her manuscript of The Year of Magical Thinking would be a best-seller, Anolik writes that “Thompson’s story shows what Joan was willing to do for the sake of her writing (anything) and what it cost her in a human sense (everything). When I said earlier that she’d crawl over corpses to get to where she had to go, I was, it turns out, speaking literally.” I’m sorry, but someone comfortable airing teenage Donna Tartt’s private letters for the sake of sensational tidbits for her podcast should take a pause.

Writing this, I hesitate—wondering I’m too soft, too defensive, if I myself am being mean. After all, Joan Didion believed that “writers are always selling someone out.” Perhaps she wouldn’t mind a little hypocritical popshot. Reading Didion & Babitz, I was undeniably enthralled—but equally disappointed. Are we really still doing this? Are we really still pitting female writers against one another and expecting one to come out victorious? It’s clear that Eve saw herself in competition with Joan, but we should do better. We should see past the petty social squabbles, painful insecurities, and thirst for validation. The story isn’t that Joan Didion and Eve Babitz had a friendship that went sour. The story is that these women were in conversation with each other—socially, in their letters, in their published work—ultimately shifting the way we make sense of a turbulent moment in American history. If we weren’t constantly pitting female writers against one another, could this have turned out differently?

A beautiful friend of mine likes to call us Joan & Eve. We hail from California and we’re always sending each other our creative work. We gripe about stagnation and cheer on the other’s successes. It’s cute. More than just cute, it’s one of the most meaningful connections in my life—both personally and artistically. I like to think of us in conversation with one another, despite working within different themes and mediums. She likes to say she’s Joan; that makes me Eve. That makes her the cool-eyed Cassandra, the lauded career writer with all the trappings of success. That makes me the undisciplined mess, running wild gathering tales, lucky to be lifted out of obscurity late in life. I try not to bristle at this. I try to laugh it off. It wasn’t meant to wound. The only judgment lurking is my own—my insecurity over my stagnation and my thirst to be seen, to be read—but depending on how I feel about my creative output at a given moment, the memory of this offhand remark comes back to wound me all the same. Even when you’re not competing, your shadow self whispers that maybe that’s the problem…maybe that’s why you’re still stalled out. This is how pervasive female competition can be.

Near the end of Didion & Babitz, Anolik sees the light:

And what if it wasn’t a competition at all? What if it was a cooperation, Joan and Eve writing L.A. together? Yes, their sensibilities were polarized, their styles clashing…Their intentions, though, were identical: to make literature that exploited what was novel and exposed what was familiar in a city, a society, and an epoch under convulsive pressure.

Yes! Finally! Three-hundred odd pages in! Yet this acknowledgement is so brief and barely considered that it made me want to fling the book across the room—especially considering how Anolik immediately shifts back into her competitive angle until she reaches the volume’s conclusion.

Putting passages from Slouching Towards Bethlehem side by side with Slow Days, Fast Company, we see Joan and Eve’s respective visions of the Santa Ana winds. Joan’s view is apocalyptic, mercurial, dangerous; Eve sees whimsy, memory, magic. To say that we need to pick a side is infuriating. Two women writing about the same thing is always going to be different, entrancing as if we’d never read about it before simply because we’re seeing something from another perspective, reading it described through a new voice. I think about what this book could have been, and I feel disappointed. There’s so much to say about Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, and I wish Anolik served her readers more than a petty feud. This disappointing misstep with Didion & Babitz is nothing new. Society has been pitting women against each other…since…always? It’s frustrating and honest and human, but I’m tired of it. You should be, too.

Lili Anolik defends her reputation as a “Literary Assassin" for Vulture.

For The New Yorker, Jia Tolentino unpacks “your body, my choice,” the dehumanizing rallying cry heralding Trump’s new era.

On TikTok, concern grows over Ariana Grande’s startling thinness, leading some to wonder whether The Wizard of Oz curse could extend to Wicked.

If traveling to the Isle of Man, always say hello to the fairies and remember that the word rat is off limits. The more you know.